"Justice cannot be for one side alone, but must be for both"

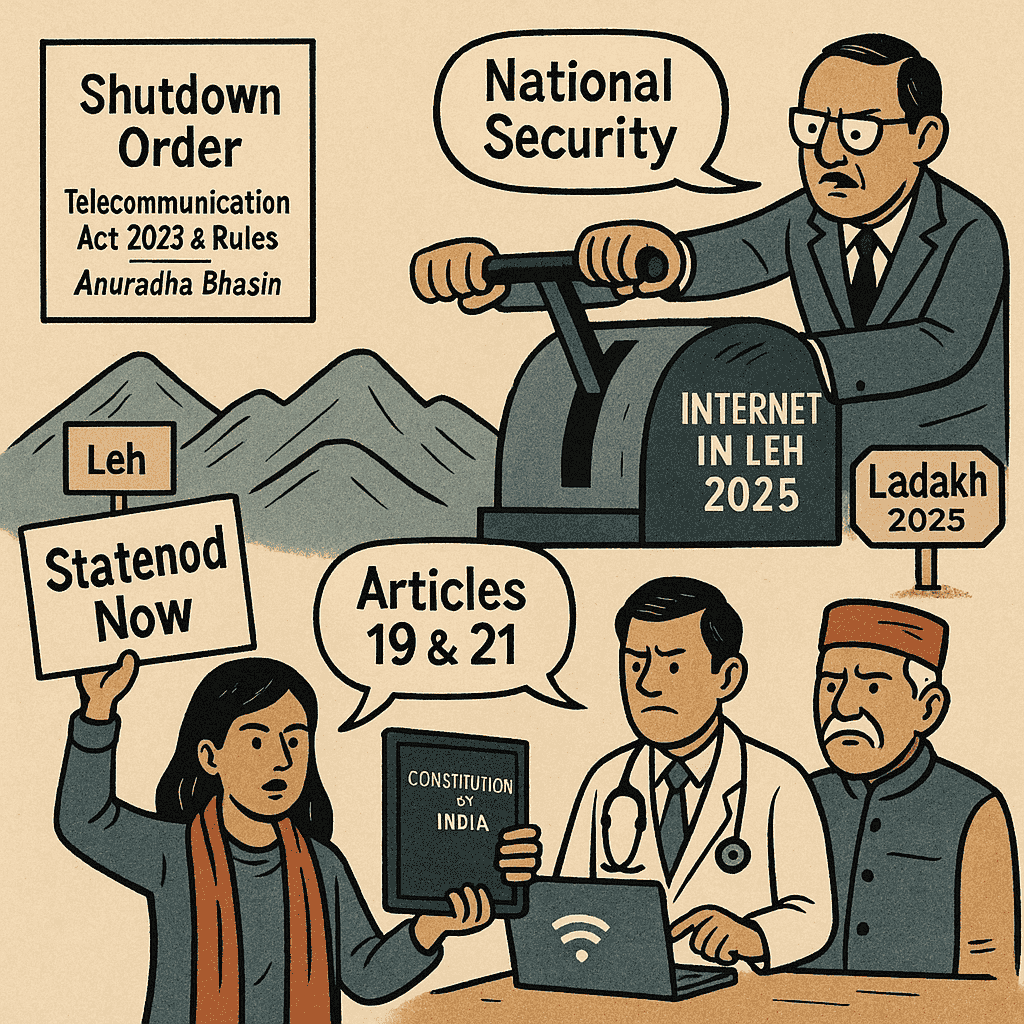

Internet Shutdowns in India: Legal Framework, Constitutional Challenges, and the Case of Leh–Ladakh (2025)

Published on : 17/11/2025

View Count : (6)

Internet Shutdowns in India: Legal Framework, Constitutional Challenges, and the Case of Leh–Ladakh (2025)

(1) Mrithunjai Sakthi Ram, Final Year B.A.LL.B., (Hons), Sastra Deemed University, Tanjore, Tamil Nadu

(2) Irfan Ahamed, Final Year B.A.LL.B., (Hons), Sastra Deemed University, Tanjore, Tamil Nadu

Introduction. In recent years India has witnessed an unprecedented proliferation of government-ordered internet shutdowns – the intentional disabling or disruption of Internet access in whole regions or nationwide. Once a novel exception, shutdowns have become a routine tool for police and political authorities to curtail communication during riots, protests, or “crisis” situations. India now leads the world in the absolute number of shutdowns[1]. This trend starkly contrasts India’s democratic commitments, including constitutional guarantees of free speech (Art. 19(1)(a)) and life and liberty (Art. 21). This article traces the evolution of India’s shutdown regime from its roots to the recent Leh–Ladakh episode of 2025, identifying gaps in the statutory framework, analyzing key Supreme Court rulings, comparing Indian law to international norms, and assessing the constitutional implications. It concludes with proposed reforms to constrain executive discretion and ensure accountability, transparency, and strict necessity in any future shutdown.

The late 2010s saw a dramatic surge. By 2018, experts were sounding the alarm that India had become the “world’s undisputed leader” in shutdowns[4]. One analysis noted that in 2018 India alone accounted for 134 of the 196 reported global outages . Since 2018 India has shut off the Internet far more often than any other country. According to Human Rights Watch, India led the world again in 2022, with 84 shutdowns out of 187 globally. Indeed, in each of five consecutive years (2018–2022) India registered the largest number of shutdowns of any country.

Several long-term conflicts have driven much of this. In the disputed Jammu & Kashmir (and since 2019, the Union Territories of Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh), shutdowns became almost routine in the mid-2010s as the state government and security forces responded to insurgency-related unrest. The longest ever democratic shutdown occurred there: after the Indian government revoked Jammu & Kashmir’s special status in August 2019, it imposed a complete communications blackout in the region. All landlines, mobile and wired Internet were suspended, ostensibly to “prevent protests”. Even as some services were restored gradually, 4G mobile Internet remained cut off for over 500 days. This one shutdown alone drew international outcry, as UN Special Rapporteurs condemned it as “inconsistent with the norms of necessity and proportionality”.

Outside Kashmir, sporadic blocks have multiplied. For instance, by 2016 dozens of short shutdowns were being ordered in states like Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Haryana, Manipur and Arunachal Pradesh for reasons ranging from communal disturbances to cheating on school exams[5]. Many were localized mobile-Internet suspensions of a few days’ duration. The government defended these as tools to prevent rumor-mongering or crime (then-Minister Jaishankar described an “internet cut” as justified if it saves lives[6]. Critics countered that these became indiscriminate and disruptive: rural communities lost access to banking, health information and welfare (the Social Security and food-ration schemes require online authentication), and even laborers in public works schemes went unpaid when net was down[7]. As one NREGA supervisor in Rajasthan lamented, “last month we worked 15 days but got paid for 12 days because the internet did not work”.

By the early 2020s the pattern was unmistakable: shutdowns were India’s first‐response “policy tool” for unrest. In Manipur (2023), Punjab (2023) and elsewhere, state governments repeatedly pulled the plug on mobile Internet to quell protests or track suspects. Even peaceful large-scale protests in Delhi and Bangalore drew shutdowns. By September 2025, as explored below, an additional shutdown was imposed in Leh–Ladakh after violent street clashes. The phenomenon now poses a pressing legal problem: India’s laws governing digital communications have not kept pace with this practice. The next parts examine that legal framework, the judiciary’s response, and how India’s approach compares to international norms. Legal and Regulatory Framework. The Indian government’s authority to disrupt communications has derived from overlapping statutes: chiefly the Indian Telegraph Act of 1885 (now revamped in the Telecom Act 2023) and the Information Technology Act of 2000. These regimes have very different scopes. Broadly speaking, website/content blocking is handled under the IT Act’s Section 69A, whereas full-network shutdowns have rested on the telecommunication laws (under erstwhile Section 5(2) of the Telegraph Act and, since late 2024, the new Temporary Suspension Rules under the Telecom Act).

By contrast, the Telegraph Act’s Section 5(2) – now embodied in Section 20(2)(b) of the Telecom Act 2023 – authorizes the government to “interfere with” the transmission of messages for reasons of sovereignty, public safety, etc. This authority was historically unbounded in duration or scope. As legal scholars observed, Section 5(2) was a blunt instrument originally used to justify anything from telephone tapping to wide-area shutdowns, and critically it “lacks [any] defined procedure when it comes to internet shutdowns”. [9]In fact, the Supreme Court had warned as early as 1997 that Section 5(2) without procedural safeguards would violate due process. For many years, emergencies or protests saw police invoke either S.5(2) telegraph orders or even Section 144 CrPC to order broad communciations curbs in entire regions (sometimes bypassing official publication requirements altogether).

It was only recently that a formal procedure was laid out for full-network suspensions. In 2017, the central government notified the Temporary Suspension of Telecom Services (Public Emergency or Public Safety) Rules, under the Telegraph Act. These Rules – now superseded by the analogous Temporary Suspension of Telecommunication Services Rules, 2024under the new Telecom Act – explicitly allow the Union or State Home Secretary (or an authorized officer) to order alltelecom services (mobile, internet, messaging) to be suspended in a specified area, but only if necessary to address a public emergency or public safety threat, or matters of sovereignty and integrity. In short, suspension orders under the Telegraph/Telecom law can shut down networks in bulk, as opposed to just blocking particular sites under Section 69A. Notably, these suspension rules require that any such order be made in writing, specify the geographic area and duration, record reasons, and be submitted to a review committee (composed of senior bureaucrats and judicial members). [10]These formalities echo the calls of the courts (below) for stricter adherence to procedure.

Thus, the distinction is clear: Section 69A ITA permits only piecemeal censorship of content by intermediaries, whereas the Telegraph/Telecom suspension rules permit broad shutdown of infrastructure by executive decree[11]. Each has its own criteria and safeguards (or lack thereof). In practice, most of the large-scale shutdowns of the past decade have been ordered under the telecommunications rules, not under Section 69A. (The IT Act has been used mainly for blocking websites or social-media accounts, not for cutting entire networks.)

Thus Section 69A cannot be used to shut off all connectivity. It does not allow the police to suspend mobile service or censor entire social media. As an oft-cited study notes, the IT Act “provides for a proportional, limited power … to issue individual web content blocking orders when certain grounds are met”. And indeed, since Shreya Singhal v. UOI (2015) the Supreme Court has treated Internet access as a constitutional dimension of free speech: one commentator notes that Shreya Singhal “recognized the Internet as an essential medium to further the right to freedom of speech and expression”. (Similarly, Anuradha Bhasin below stressed that access to Internet is a part of constitutional free speech.) In sum, the Section 69A power – while broad enough to target any online information deemed dangerous – is far narrower in compass than the network suspension power under telecommunication laws.

Yet even under the new rules the state wields immense power. The Union Home Secretary (or State Home Secretary) can issue a shutdown on finding a “public emergency” or “public safety” need[13]. The terms are broad. In practice, recent shutdown orders have cited “unavoidable circumstances” and the need to “avert public emergency and prevent incitement”. As will be discussed, courts have mandated that such orders must also satisfy Article 19(2)’s test of “reasonable restriction” (necessity and proportionality). Without judicial check, however, the suspension rules risk being rubber-stamped in the name of vague security.

In summary, the legal framework for Indian shutdowns is fragmented and ad hoc. Content censorship (69A) and network suspension (Tele Rules) originate in different statutes with different procedures, and neither was originally designed with modern Internet shutdowns in mind. Section 69A explicitly empowers only targeted content bans; the suspension rules allow blanket cuts for broad reasons. Crucially, no single law explicitly enshrines the principles of necessity, proportionality, and minimality that the courts would later impose, nor any independent oversight mechanism beyond the internal review committees. This gap in the statutory scheme—lack of an explicit, transparent regime of safeguards—is the central research problem. To address it, one must consider how the judiciary has straitjacketed the executive’s powers and how Indian norms measure against international standards.

In Anuradha Bhasin v. Union of India[i], a group of Kashmiri journalists challenged the 2019 communication blackout in Jammu & Kashmir[14]. On January 10, 2020 the Court delivered a seminal judgment. It held that freedom of speech and expression under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution includes the right to access and impart information via the Internet. The Court therefore insisted that the government could not indefinitely suspend Internet services merely by executive fiat. Any communication shutdown, it ruled, must be subjected to the “test of proportionality” under Article 19(2) – i.e. the restrictions must be reasonable, necessary, and proportionate to a valid state interest[15]. Specifically, the Court declared that a blanket, indefinite suspension of mobile internet was impermissible. Under the then-applicable 2017 suspension rules, orders could be “temporary” only, and the duration had to be limited to what was strictly needed. The Court stressed that each shutdown order must state its precise grounds and be published, so that those affected can challenge it in court. In effect, Bhasin laid down that shutdown orders must be “lawful, necessary and proportionate” and limited in time, echoing tests for other free-speech restrictions[16]. The Court also clarified that Article 19 protections were not suspended even during the Jammu & Kashmir emergency; free speech rights remain alive and judicially enforceable.

Foundation for Media Professionals v. Union Territory of J&K (often called the “4G judgment”) followed a few months later (May 2020). Here petitioners challenged the refusal to restore 4G mobile Internet in J&K during the COVID-19 lockdown, arguing the continuing 2G-only regime violated rights to health, education, and information. The Supreme Court acknowledged that livelihoods, health care, and education were adversely impacted by poor internet speeds, and that “modern terrorism heavily relies on the internet”. [17]Yet the Court ultimately upheld the state’s order, noting that “national security concerns” and the prevention of fake news had to be balanced against fundamental rights. The Court reiterated Bhasin’s proportionality approach: any shutdown must be confined to only what is absolutely necessary. It faulted the J&K government for issuing a “blanket order” affecting the entire region rather than tailoring restrictions to specific high-risk areas[18]. In particular, the Court observed that “the degree of restriction and the scope of the same, both territorially and temporally, must stand in relation to what is actually necessary to combat an emergent situation”. It held that the government must justify why 4G was not needed anywhere in the territory, a showing J&K had failed to make in record. Importantly, FMP affirmed that shutdown orders are subject to judicial review (contrary to government assertions that security was “beyond the purview” of courts).

Both cases thus impose rigorous constraints on the exercise of shutdown powers. From Bhasin derives the core principle that unrestricted, indefinite shutdowns violate free speech; from FMP comes a strict necessity/proportionality mandate. Together, they enshrine the requirements that any communications blackout must have clear legal authorization, be grounded in concrete facts, be strictly time-limited, and be reviewed. The rule of law demands that no one’s net access be cut off except by law for compelling reasons – a result echoed in both domestic courts and international bodies.

One further notable Supreme Court case should be mentioned for context. In People’s Union for Civil Liberties v. Union of India (1997) the Court addressed telephone-tapping and pointed out that Section 5(2) of the Telegraph Act (on which later shutdown rules are based) was unconstitutional in the absence of procedural safeguards. That judgment (and related telegraph jurisprudence) underpins much of the modern critique: until 2017, Indian law effectively permitted telephones and internet to be shut down by executive fiat, which the courts warned could violate liberty without legislative curbs. Thus, even before the Bhasin era, judges had struck down overly vague surveillance powers, setting the stage for more expansive free-speech rights in the digital age.

In Europe, the Court of Human Rights has similarly protected broad Internet access. In Ahmet Yildirim v. Turkey (2012), the European Court struck down a sweeping block of Google Sites by Turkish authorities. The court stressed that the Internet “has now become one of the principal means of exercising the right to freedom of expression and information”. A blanket injunction that shut down an entire service was found disproportionate absent a precise legal framework and proof of necessity. The court held that “such a measure [rendering] large amounts of information inaccessible must be considered a direct effect on the rights of Internet users” and requires “strict legal framework” and “judicial review” to prevent abuse. This echoes Bhasin’s insistence on strict legal procedure[21].

In the United States, the First Amendment offers robust protection to digital speech. While there is no precedent for federal shutdowns of the Internet (the US Constitution strongly disfavors content-based cuts), American law underscores that Internet intermediaries are generally treated as common carriers or neutral conduits, free to carry traffic without editorial interference by the state. The FCC’s net-neutrality regulations (now in flux) and judiciary have long recognized the political salience of unfiltered information flow. In practice, US authorities have relied on less blunt methods (targeted law enforcement, national emergencies measures) rather than nationwide blackouts. For instance, after the 9/11 attacks the US passed the Patriot Act and FISA Amendments Act to surveil communications, but did not turn off networks en masse. Even proposed bills or state-level measures to cut off certain content (e.g., combatting online “censorship” by foreign actors) have raised red flags under U.S. free-speech principles.

In sum, international norms view Internet shutdowns with extreme skepticism. UN and European standards stress that any digital shutdown is an extraordinary measure that must be justified by compelling evidence and procedural safeguards. India’s Bhasin and FMP decisions are largely in line with this global consensus, insisting on necessity, proportionality and written justification – the exact elements spotlighted by UN Resolutions and Court opinions. By contrast, India’s historical practice had fallen well short. Thus, the international perspective strengthens the argument that India’s ad hoc shutdown regime needs urgent legal reform to meet these minimal democratic standards[22].

After six days, on October 4 the administration formally announced the restoration of Internet access, describing it as “good news” following deliberations with local groups. The shutdown thus lasted roughly five days. The order appears to have been issued by the District Magistrate and approved by the Ladakh UT Home Secretary, as required under the new rules. Press reports confirm that it invoked “unavoidable circumstances” and “public order” as grounds – language consistent with the statutory scheme[24].

Legal Basis. Crucially, the Leh shutdown was effected under the new telecommunications law: the official order cites the Telecommunications Act, 2023 and the 2024 Suspension Rules (which replaced the 2017 Rules). Under Section 20(2)(b) of the 2023 Act, the Union or State government can suspend telecom services on grounds of public emergency or public safety, or to prevent incitement to offences. The 2024 Rules specify that only the Home Secretary (Union or State) or an empowered officer may make such an order, and that it must be justified in writing with stated reasons. In this case, the appropriate process appears to have been followed on its face: a formal written order was issued (at least to the service providers), and it was publicized by media accounts. There was no legislative authorization beyond the Act and rules – indeed no new ordinance or Act was needed because the 2023 statute already empowered such actions.

Constitutional Analysis (Art. 19 and Art. 21). The interim shutdown posed immediate questions under the Indian Constitution. First, Article 19(1)(a) guarantees freedom of speech and expression, which the Supreme Court has expressly held to include digital communication.[25] Restricting Internet access directly curtails that freedom. Accordingly, any suspension must satisfy Article 19(2) – it must be on a valid ground (e.g. “public order” or “security”) and be reasonable and proportionate. The Leh administration invoked “public order” and “incitement” in its order (though the text uses broader “public safety”), which are among the exceptions in Article 19(2). These citations mirror the language of the Telecom Act rules and Article 19. Whether they meet the constitutional requirement of immediacy and necessity is another matter.

Under Anuradha Bhasin, shutdowns of short duration are not per se unconstitutional, so long as they are truly temporary and justifiable. Here the five-day duration appears to respect the statutory ceiling (15 days) and is not indefinite. The authorities would argue that in the immediate aftermath of deadly riots it was necessary to prevent viral rumors or panic calls that could spark further violence. The scope was limited (to Leh district) and purely mobile data (not even affecting landline telephony or 2G voice). On its face, one could argue this is an exercise of lawful power to maintain order, using the least restrictive means available given the urgency.

However, applying FMP’s logic, the key questions are: (1) Necessity – Was cutting off data genuinely needed to restore order? (2) Proportionality – Was a wholesale shutdown the narrowest measure, or could the state have used less restrictive options (e.g. targeted arrests or content takedown)? (3) Reasoned Justification – Did the order articulate concrete facts to support it, or was it vague? While government statements cited “unavoidable circumstances” and “preventing incitement”[26], publicly available reports do not detail specific incidents of social-media abuse or the extent of riot-mobilization on internet channels. This opaque rationale echoes criticisms raised in other states: studies have found many Indian shutdown orders rest on “vague apprehensions” rather than concrete evidence[27]. Without transparency, Leh’s residents have no way to assess whether the shutdown truly met a pressing emergency test.

From the perspective of Article 19 jurisprudence, FMP emphasized that even during a crisis, the geographic and temporal scope of a shutdown must not exceed the minimal needs. The Leh order did limit itself geographically to Leh (not all of UT Ladakh) and was time-bound (five days). Those are positive signs of proportionality. Yet FMP also insisted that the Executive show why restrictions could not be partial; notably, in Leh the curfew on movement had already been imposed. Could authorities have achieved their goals by policing curfew areas and ordering specific social-media accounts removed, rather than silencing the entire Internet? The Supreme Court in FMP asked why 4G needed to be suspended in all districts of J&K.[28] Similarly, one could argue the Leh order should have explained why mobile data had to be cut even in parts of Leh that were peaceful, or why it could not be lifted sooner.

Article 19 also contemplates a procedural safeguard: restrictions must be by “law” and on published orders. Here the shutdown was ordered under valid law (Telecom Act and Rules), but Anuradha Bhasin requires that orders be put on record and made available to the public to enable challenges. It is unclear whether the Leh suspension order was ever gazetted or published beyond media reports. Without formal publication, the affected population would struggle to litigate the order’s legality (exactly the defect Bhasin warned against).

Article 21 (“personal liberty and life”) has not been squarely adjudicated in the context of brief internet blackouts, but an argument can be made that it too was engaged. The right to life has been expansively interpreted to include a dignified existence and livelihood. Cutting Internet service impacts education, health (e.g. telemedicine), businesses, and government services. For instance, many government welfare schemes and healthcare registrations now require Internet access. The Human Rights Watch report on shutdowns documents how suspensions left people unable to access food rations or pay wages[29], affecting rights to livelihood and food (matters connected to Article 21). In Leh’s case, five days may seem short, but even a brief outage can harm mountain communities: farmers rely on market data via phones, and students use online resources. Moreover, FMP petitioners had argued that at least partial shutdowns violated health and education rights during a pandemic. By analogy, one might say Leh’s blackout interfered with the citizens’ ability to live according to normal constitutional guarantees. The Court in FMP did not explicitly invoke Article 21, but it recognized that free flow of information is often a prerequisite to other rights.

Ultimately, the Leh shutdown’s legality under Articles 19 and 21 depends on how strictly one applies the proportionality test. If a court were to scrutinize it, it might find that the executive’s action was within the broad ambit of authority but fell short of the transparency and justification demanded by Bhasin/FMP. In any event, the episode starkly highlights the tension between governmental claims of emergency and the need for accountable safeguards. As one commentator observed in a similar context, “[i]t is a trust deficit when shutdown orders are not published and are solely based on the fear of rumours”. The Leh case exemplifies this dilemma: security concerns loomed large, but the absence of public scrutiny means we cannot fully assess whether the balance tipped correctly.

These practices expose the gaps in Indian statutory law. First, there is no standalone statute that defines “internet shutdown” or sets out detailed criteria. Instead, shutdowns lie at the intersection of telecommunications and IT law, a fragmentation Congress never fully resolved. This led to unclear jurisdictional lines. For example, before the 2023 Act it was arguable whether the Telegraph Act applied to all forms of Internet (fixed and mobile) or only to voice messages. The new Telecom Act is broader, but even today a state internet shutdown might rest on telegraph law (now telecom law) while Section 69A (central law) is treated separately. In theory, Parliament could enact a specific “Internet Services Act” to unify these provisions, but it has not done so.

Second, existing laws lack robust remedies for those harmed. Courts have asserted jurisdiction (for example, Bhasininvolved writ petitions), but the statutes themselves contain no express appeal or remedy for shutdown victims. Contrast website-blocking under 69A (where affected parties can appeal to a tribunal) with telecom suspensions (no similar route is provided by statute; one must resort to fundamental-rights litigation). Legislative reform could fill this gap by ensuring a clear, expedited review process (perhaps a specialized tribunal or fast-track mechanism) for challenging shutdown orders.

Third, the criteria in law remain overbroad. The enumerated grounds (sovereignty, integrity, public order, incitement) are sweeping. Bhasin and FMP tried to narrow them through interpretation, but a statute should clarify that “public order” means imminent threat of violence, that “incitement” requires clear nexus to an offense, etc. The 2024 Rules at least require that reasons be recorded and orders be kept brief, but they do not precisely define how “necessary” is to be shown. There should be a higher evidentiary threshold and perhaps mandatory inter-departmental review before a shutdown.

Fourth, the human-rights safeguards need strengthening. Critics have urged that all shutdown orders be automatically published and made available to the public and to courts without requiring RTI petitions. One legal analysis bluntly states that “the government must make all shutdown orders publicly accessible…providing clear explanations for the suspension in the regional language”. This simple reform – already partially required by current rules – would allow citizens to know the exact legal basis of any outage. Additionally, there should be penalties for non-compliance: if authorities illegally order or extend a shutdown, individuals or companies that suffer losses should have a clear right to compensation or judicial relief.

Fifth, oversight must be genuinely independent. The 2017 and 2024 Rules mandated review committees with retired judges and senior bureaucrats.[30] This is a step forward, but in practice these committees often meet well after a shutdown and lack enforcement teeth. Reform proposals include requiring that such committees automatically stay any extension beyond 15 days unless they affirm necessity, and that their findings (with minutes) be published. Some have even suggested inserting judicial pre-approval for any shutdown: akin to the way wiretaps require magistrate sign-off, telecom shutdowns could require ex ante judicial sanction in high-risk cases (perhaps via dedicated emergency bench). While the courts in FMP did not expressly mandate a judicial review at the front end, nothing prevents Parliament from building such a mechanism into law to avoid ex post litigation.

Finally, broader policy measures should counterbalance the executive’s impulse to shut off the net. Many experts advocate data-driven accountability: for example, Human Rights Watch calls for a national database of all shutdowns. This registry would log every suspension order, its stated reason, duration, and outcomes of any review, and make the information public. Such transparency would enable empirical analysis of shutdown frequency and effects, pressuring authorities to justify each case. Another idea is to treat Internet access as an essential service (similar to water or electricity) once net penetration reaches a certain threshold. Under this view, cutting off connectivity would require not only high-level approval but also compensation obligations or automatic arbitration.

In addition, technological and procedural reforms can mitigate the need for future shutdowns. Instead of blunt blackouts, authorities should develop targeted content moderation and fact-checking platforms (investing in counter-misinformation networks rather than disabling the entire medium). The private sector too has a role: social-media companies should resist blanket filtering demands and insist on granular orders. Multi-stakeholder dialogue (government, civil society, industry) could yield standard operating procedures that allow authorities to address security risks without halting civilian communication – for example, rapid DMCA-style takedown procedures for clearly unlawful content in emergencies.

In doctrinal terms, the “gap” in Indian law is the lack of explicit statutory incorporation of the Bhasin/FMP standards. These should not remain mere judicial dicta. Ideally, Parliament would amend the Telecom Act to require that any suspension order explicitly cite the material facts justifying “imminent danger,” limit orders to no more than 15 days (or the maximum needed), and automatically trigger judicial review upon issuance. Parallel amendments to the IT Act could similarly tighten Section 69A by clarifying that its block orders must also satisfy a strict test (some bills have been introduced in past sessions toward this end). In short, India needs a comprehensive Communications Emergency Act that enshrines accountability measures for any digital curfew.

To summarize the main reform proposals: -

Mandatory Publication and Transparency: All shutdown orders (and reviews of them) should be published promptly, with clear reasons[33]. Victims must have timely access to challenge orders. -

Time and Scope Limits: Entrench short duration caps in law (e.g. max 15 days, renewable only after review), and require orders to precisely define the affected area. Judicial Oversight: Introduce automatic judicial review or at least immediate remedy options (e.g. writ jurisdiction or special tribunal) for shutdowns. Possibly a mechanism of ex ante judicial authorization for sensitive cases. -

Clear Grounds and Evidence: Narrow “public order” and “incitement” definitions in statute, and require factual demonstration (not just “fear of mischief”). -

Independent Review Committees: Enhance the role of multi-member committees (with retired judges) by having them report publicly and bar continuations absent their concurrence. -

Accountability and Remedies: Provide cause of action for affected users/businesses, and penalties for officers who exceed their powers. If a shutdown is found unlawful, victims should be able to claim costs or damages. -

Data Recording: Maintain a government database of shutdowns including detailed metadata (duration, reasons, lost hours), to enable parliamentary or judicial scrutiny. - Staggered Response Options:Encourage adoption of less-restrictive measures (like bandwidth throttling or targeted URL blocking) in place of total blackouts whenever feasible.

Implementing these reforms would narrow the executive’s discretion and internalize transparency. It would put teeth behind the Supreme Court’s requirements, which have so far been only aspirational. It would also harmonize India’s practice with the global trend toward treating Internet access as a protected right rather than a brute-force control.

The Leh–Ladakh case of September 2025 illustrates both sides: a real crisis invoked a lawful-appearing suspension under the 2023 Act, yet it also spotlighted the opacity and potential overbreadth of such curbs. If this shutdown were tested in court, the outcome would depend on fine judgments of necessity and evidence – judgments that Indian statutory law should have made more straightforward.

Ultimately, robust democracy demands that digital expression be cut off only with great caution. As the United Nations has declared, intentional Internet shutdowns “undermine and pose a serious challenge to the enjoyment of human rights”. To honor its constitutional commitments, India must enshrine the Bhasin/FMP principles in law: no shutdown without legal authority, publication, strict necessity and limited duration. By embedding transparency and judicial accountability in the shutdown regime, Parliament and the executive can narrow overreach and prevent the erasure of citizens’ rights whenever the Internet waves are at storm. The legislative and policy reforms sketched above are urgent steps toward that goal – steps that will ensure India’s shutdowns are a last resort, not a default response.

References

[1] Safi, M. (2019, December 19). India’s internet curbs are part of growing global trend. The Guardian.

[2] See supra note 1

[3] Gupta, A., & Chima, R. J. S. (2016, October 25). The cost of internet shutdowns. The Indian Express.

[4] See supra note 1

[5] See supra note 3

[6] Bajoria, J. (2023). “No internet means no work, no pay, no food.” In Human Rights Watch.

[7] See supra note 3

[8] Southey, A. (2023, April 13). The Online Regulation Series | India.

[9] See supra note 1

[10] Walia, H., Chandan, A., Chandra, S., & Goel, K. (2024, October 14). ERGO analysing developments impacting business: Government publishes rules for temporary suspension of tele. . .

[11] See supra note 8

[12] See supra note 10

[13] India, S. (2025, May 6). Unlawful expansion of internet shutdown powers in India. Internet Society Pulse.

[14] Anuradha Bhasin Judgment on internet shutdown. (n.d.). Drishti Judiciary.

[15] Access Now, Association for Progressive Communications (APC), & Internet Freedom Foundation (IFF). (2021).

[16] See supra note 14

[17] Columbia Global Freedom of Expression. (2023, November 10). Foundation for Media Professionals v. Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir & Anr. - Global Freedom of Expression. Global Freedom of Expression.

[18] See supra note 17

[19] Shutting down the internet to shut up critics. (2020, January 14). Human Rights Watch.

[21] See supra note 20

[22] See supra note 20

[23] Ganai, N. (2025, October 10). Internet services restored in Leh. The Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/internet-services-restored-in-leh/articleshow/124464044.cms#:~:text=After%20the%20violence%2C%20authorities%20in,Kargili%20of%20Kargil%20Democratic%20Alliance

[24] See supra note 8

[25] Anuradha Bhasin Judgment on internet shutdown. See supra note 14

[26] See supra note 8

[27] Digital Rights Society, Unlawful Expansion of Internet Shutdown Powers in India, Pulse (Internet Society) (May 6, 2025), https://pulse.internetsociety.org/blog/unlawful-expansion-of-internet-shutdown-powers-in-india

[28] Columbia Global Freedom of Expression. (2023b, November 10). Foundation for Media Professionals v. Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir & Anr. - Global Freedom of Expression. Global Freedom of Expression.

[29] See supra note 14

[30] Walia, H., Chandan, A., Chandra, S., & Goel, K. (2024b, October 14). ERGO analysing developments impacting business: Government publishes rules for temporary suspension of tele. . . Lexology. https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=255efc06-c1a0-444d-9225-27c598340f20#:~:text=5,Committees

Journal Volume

You should always try to find volume and issue number for journal articles.

Nyayavimarsha

No. 74/81, Sunderraja nagar,

Subramaniyapuram, Trichy- 620020