"Justice cannot be for one side alone, but must be for both"

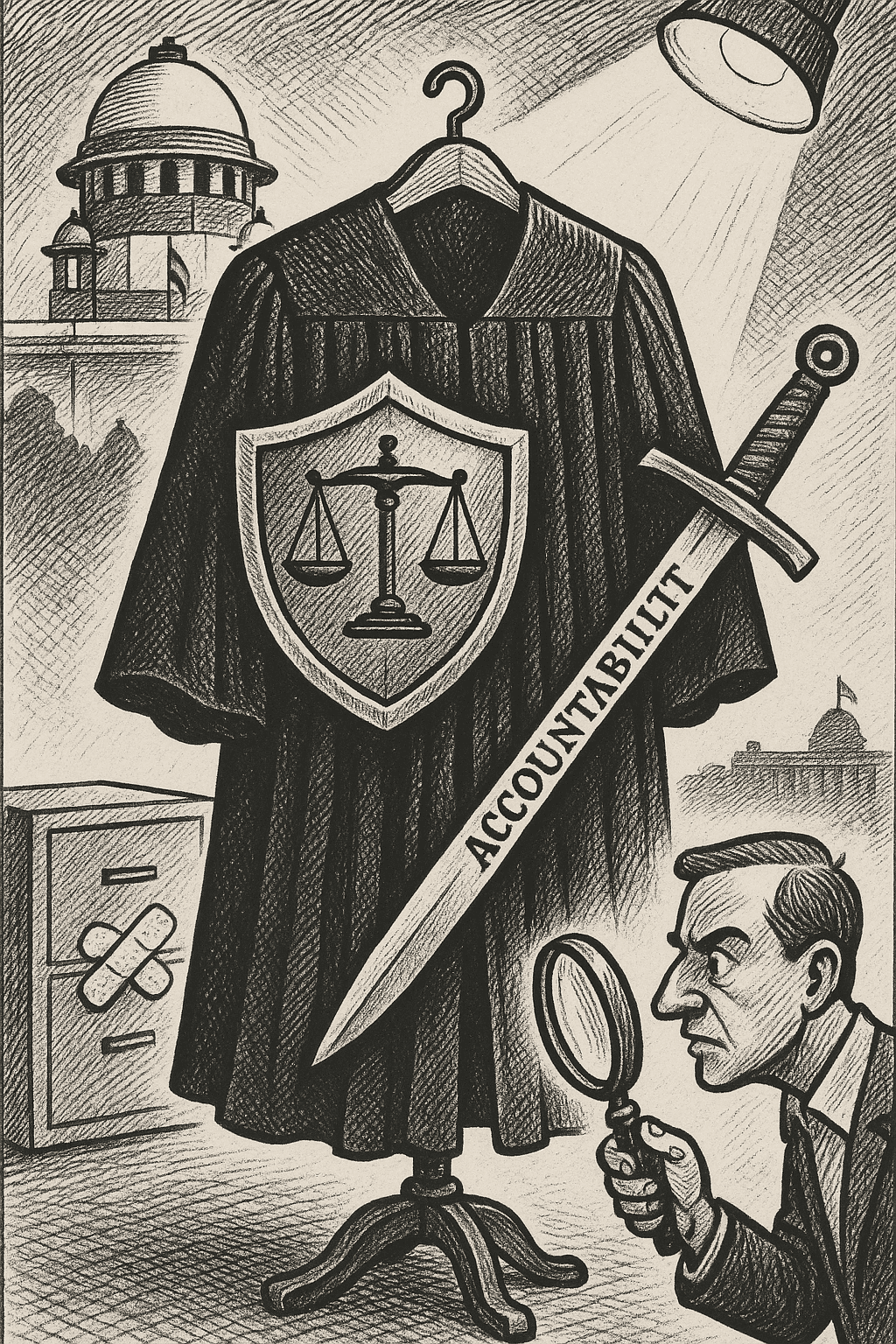

The Limits Of In-House Justice: Evaluating India’s Mechanism For Handling Judicial Misconduct

Published on : 05/10/2025

View Count : (14)

The Limits Of In-House Justice: Evaluating India’s Mechanism For Handling Judicial Misconduct

The Limits Of In-House Justice: Evaluating India’s Mechanism For Handling Judicial Misconduct

Author Details

Ms. Rujula Kapoor,

2nd year B.B.A. LL.B.,

IIM Rohtak

Introduction

We continue to hear that judicial independence is essentially the plank of constitutional democracy. The high courts have significant powers to review and interpret the constitution in India and hence they are the ultimate procession of the fundamental rights.

However the enormous power comes with a responsibility to be responsible. Raising such a paradox, when the media addresses misconduct against serving judges, how can judges be held accountable without exposing them to external or political pressures that might compromise judicial independence?

This is a predicament that has bedeviled Indian constitutional practice. Judicial removal can only be done formally by impeachment on Article 124(4) of the Constitution, which is such an extreme and burdensome remedy that it has been applied infrequently.[1] The Supreme Court of India acknowledged the necessity of more gentle treatment when it, in 1999, launched an internal methodology, a system created by the judges, which was to address the allegations of misconduct.[2] The procedure is based on secrecy and ethical persuasion, the investigation is chaired by teams of judges, and the findings are not normally publicized.

Although the in-house process was meant to protect the judiciary against political influence, the process and formation thereof have continued to receive critical reviews. The opponents claim that it is not legally supported, works behind the scenes, and is a peer-reviewed process, which leads to the issue of conflict of interest.[3]

The paper assesses the weakness of in-house justice as a tool of redressing judicial misconduct in India. It poses the question of whether the in-house accountability is enough to maintain the social trust, and claims the necessity of the conduction of significant reform to reconcile independence and accountability

Judicial Misconduct: Concept And Context

Judicial misconduct can be described as any action of a judge, which contravenes the ethical norms of his or her office. This malpractice will compromise fair administration of justice. It may be in numerous ways: corruption and bribery, nepotism, adjudication bias, sexual harassment, inappropriate personal behavior, and misuse of judicial office to personal advantage.[4] Due to the extraordinary powers of the judges and the need to uphold the utmost standards of probity, even the slightest impression of misconduct may seriously damage the perception of the rule of law.

According to the constitution framework in India, there is little justification of the removal of judges in the Supreme Court and High Courts. Article 124 (4) of the Constitution is that a judge can be dismissed only by an order of the President, which must be passed, following an address by Parliament, on grounds of proved misbehaviour or incapacity.[5] Article 124 (5) authorises Parliament to prescribe the procedure, which it did in the Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968, and the Judges (Inquiry) Rules, 1969.[6] Nonetheless, it is a cumbersome process and hardly ever successful; the issue of accountability is often overlooked in favor of politics.

Judicial misconduct in India is demonstrated through a number of high-profile cases. In K. Veeraswami v. The Supreme Court of India ruled that judges of higher courts could be prosecuted under the Prevention of Corruption Act only after receiving an emergency sanction by the Chief Justice of India, and therefore limited scrutiny by outsiders.[7] Over the more recent, sexual harassment against sitting Supreme Court judges has cast doubt on whether self-regulation mechanisms by the judiciary would inspire confidence in the judiciary.[8]

These scandals demonstrate that judicial legitimacy is not only rooted in judicial independence, but also is rooted in the perceptions of judicial misconduct held by a court. In the absence of plausible checks and balances, independence may be confused with impunity, undermining the very degree of trust which forms the basis of court power.

The In-House Process: Development And Model

In-house procedure was introduced in 1999[9] by the Supreme Court of India upon the discovery that impeachment was not sufficient to deal with claims of judicial misconduct and it offers a system to be used to address complaints leveled against Supreme Court and High Court judges, without necessarily having to impeach them. It is not a legislative mechanism but a judge-made one[10] as opposed to the Judges (Inquiry) Act of 1968.[11]

A complaint against a judge of the High Court in the procedure is first submitted to the Chief Justice of that court. In case the complaint seems to be a serious one, the Chief Justice can send it to the Chief Justice of India (CJI). The CJI then establishes a three-member committee of senior judges of other High Courts to probe into the matter.[12] In a complaint made against Supreme Court judges, the CJI appoints a three-member committee of Supreme Court judges. Such committees work on high levels of confidentiality, and are only concerned with fact-finding and recommendations.

The in-house process is therefore, internal, confidential and non-binding. It does not attract sanctions that are legally binding. Rather, the committee can advise the judge, either to resign or retire voluntarily.[13] When a judge declines to do so, the only option that is left is to impeach the judge in the constitutional process. The system is thus based on the ethical power of peer review as opposed to the obligation of the law.

The in-house mechanism has several major characteristics. First, it maintains the process in the judiciary which preserves the judges against political influence. Second, it does not need to be publicly disclosed, inquiry reports are frequently withheld even by the complainant. Third, it focuses on voluntary compliance, which includes no disciplinary measures except possible expulsion by Parliament.[14]

This system, according to its proponents, has significant strengths. This preservation of judicial independence by avoiding outside interference by the executive or legislature. This is because the process remains confidential and frivolous complaints or those based on political motives do not affect the credibility of the judiciary. Besides, peer inquiry can be more effective and less confrontational as compared to impeachment actions.[15]

However, though the in-house process indicates the true desire of the judiciary to self-regulate, its informal and advisory character casts doubts on the capacity of the in-house process to provide adequate transparency and accountability in a constitutional democracy.

Drawbacks of the in-house procedure

Although the in-house process was devised to help resolve a critical vacuum in the judicial accountability model in India, its functioning has severe limitations. These weaknesses raise questions on its ability to be a viable tool in controlling judicial wrongdoing.

The most notable criticism about in-house procedure is its secrecy. All of the complaints, inquiries, and discoveries are maintained secret, and the results are seldom disclosed to people, including the complainant.[16] This is because secrecy is supposed to safeguard the independence of the judiciary and guard the judges against baseless accusations; however, too much secrecy leads to mistrust. Questions cannot be evaluated as fair, impartial, and even complete without publicizing the same. Such lack of transparency impairs the credibility of the judiciary and destroys the confidence of people in its self-regulation.

The other major shortcoming is that the procedure lacks constitutional or statutory basis. It is a judicial procedure, developed by a Supreme Court resolution and not by Parliament.[17]Consequently, it does not have a legal enforcement power and cannot enforce lawful penalties. Its advisory form makes it a kind of moral persuasion which relies on the voluntary obedience of the judge.[18] The fact that it is not supported by the law undermines its efficacy and makes one doubt its legitimacy.

The process is condemned to be biased in its nature since it is the other judges who are questioned. Judging the judges may result in leniency or conflict of interest particularly in a close-knit judicial system.[19] Although questionings are extensive, the perception of the bias destroys the trust of the people. In other democracies, e.g. the United Kingdom and Canada, judicial complaints are processed by independent bodies representing people outside the system- a feature that lacks in the Indian system.[20]

The lack of enforceable sanctions is the greatest limitation. Inquiry committees can advise that a judge should resign or retire at his own free will, but cannot enforce him.[21] In case of refusal by a judge, the only way is to impeach him/her by Article 124(4) of the Constitution, which is a very high standard to meet. Judges that are accused of having bad behavior are thus able to stay in office despite the fact that their allegations are verified to be serious.

The in- house system is fully an internal judicial system. After a complaint has been lodged, the civil society, independent experts, or even the complainant does not have a part to play.[22] This lack of accountability is counterproductive to international best practice, in which transparency and external controls are vital due to lack of confidence.

Weaknesses Of Citizen Trust: Case Study.

These limitations are exhibited by a number of controversies. In the example of Justice C.S.Karnan of the Calcutta High Court, decades of unpredictable actions and accusations of misconduct have forced the Supreme Court to use contempt proceedings and incarcerate him, a move unprecedented in terms of accountability that brought into perspective the inefficacy of the current accountability procedures.[23] The inquiries into sexual-harassment claims against serving Supreme Court judges that came out recently also revealed a lack of transparency in the in-house process that attracted mass criticism among women-rights-groups and overall society because of its perception as an institution that protects its own.[24]

A combination of these restrictions is a disturbing fact. Although the in-house process was meant to maintain the independence of the judiciary, its discretion, absence of legal sanctions as well as its closed nature have eroded its credibility. Quite to the contrary, the system has been seen to work against public expectations by seeming to favor the judges at the cost of judicial accountability, which reduces trust in the judicial system as a whole.

Comparative Perspectives

By looking at other democratic jurisdictions, it is revealed that judicial accountability mechanisms can be crafted in such a way as to enhance judicial independence, as opposed to undermining it. Compared to the in-house process in India, most countries have established statutory frameworks that incorporate independence and transparency and enforcing practices.

UNITED KINGDOM

In the United Kingdom, the Judicial Conduct Investigations Office (JCIO) is the body that deals with judicial misconduct. The JCIO was introduced by the Constitutional Reform Act, 2005[25], and it is an independent statutory organization. It receives complaints, investigates the cases and proposes punitive measures against judges. The JCIO releases yearly reports and in severe instances, it makes public statements concerning outcomes.[26] This openness means that the judiciary is checked and balances the political abuse of the process, since ultimate decisions incorporate both the Lord Chancellor and the Lord Chief Justice working together.

UNITED STATES

Another example is provided by the United States by the Judicial Conduct and Disability Act of 1980. The Act gives Judicial Councils in every federal circuit the power to examine the complaints brought against the judges.[27] Complaints can be dismissed, handled informally or made to undergo a formal investigation. The Judicial Conference of the United States can review the appeal.[28] It is a system which focuses on internal judicial self-control, but has procedural protections in the form of a right of appeal and the making of orders publicly available on major cases, as well as balancing accountability with independence.

CANADA

Federally appointed judges in Canada are subject to complaints by the Canadian Judicial Council (CJC) which was established by statute in 1971.[29] The CJC resorts to investigating the misconduct allegations and can suggest the removal of a judge to parliament. It publishes comprehensive public reports on investigations, which contribute to transparency and citizen trust.[30] The Council also undertakes proactive activities including coming up with ethical provisions and provision of educational materials to judges, which is a preventive aspect that is not part of the Indian model.

Possible Reforms For India

The existing in-house procedure in India has got its boundaries. The system would be more credible, transparent and enforceable by having a statutory framework that is enacted by the parliament. The comprehension of complaints, inquiries, and discipline could be achieved in a modeled law of Judicial Standards and Accountability Bill, 2010, although it was never passed. It would enhance its authority and public acceptability as it would be statutory.[31] It would also be necessary to have an independent Judicial Oversight Commission. The judiciary, the executive, the legislature, and the civil society should have balanced representation within the commission to ensure that the commission does not merely turn out to be a peer-shielding institution.[32] It may also adopt the structure of the existing bodies like the Judicial Conduct Investigations Office of the UK and Judicial Council of Canada, which combine both internal and external controls to increase the trust of people.[33]

There should also be an enhancement of transparency. Although confidentiality may be necessary in investigation to safeguard judicial integrity, the ultimate findings of investigations must be revealed, even in the redacted version. The judiciary is empowered in this practice, which judges use in Canada and the UK, by ensuring that the judiciary does not deal with trivial or politically agenda motivated complaints, such as screening at preliminary and punitive measures against abuse of the process.[34] Another reform that is very important is graduated sanctions. In the present case, a judge suspected of misconduct has only two alternatives, voluntary resignation or impeachment by following Article 124(4) of the Constitution. A reform system must provide commensurate punishments- warnings, temporary suspension, compulsory counseling or limitations on some of the judicial functions- to ensure that accountability is upheld without necessarily damaging careers because of negligible misconduct.[35]

Strong whistleblower policies are also required. Attorneys, court officials and claimants who file grievances should be protected against revenge. It is only through this kind of protection that actual grievances can be expressed and dealt with.[36] Measures that are preventive are also crucial. The judicial system must embrace a binding code of ethics, and also have regular training on professional conduct, integrity, and gender sensitivity.[37] The ongoing judicial education (as in Canada and the United States) is not only a deterrent to misconduct but a way to enforce ethical standards[38] One way in which India can make use of technology is through developing an online resource in terms of tracking complaints. This would enable complainants to know how their cases are progressing without revealing the cases and such a system would affect perceptions of arbitrariness and increase accountability.

The combination of these reforms would help bring India out of the veil of secrecy in the in-house procedure to a system of statutory, transparent and independent accountability. External checks and balances, including proportionate sanctions, would keep the judiciary not only at bay but also create greater independence through an added level of public trust.

Conclusion

The dilemma faced by India in the fight over judicial independence and accountability revolves around autonomy and judicial accountability. The in-house process of 1999 was to deal with misconduct but not with judicial independence. Nevertheless, it is not very effective since it has several limitations, such as lack of transparency, absence of statutory basis, peer reviewing, and no sanctions that may be actually enforced. The veil of mystery surrounding its activities, the absence of inclusion of the civil society, and complainants has also generated more nervousness among people as to whether the judiciary is ready to apply the same judgment on itself.

A comparison of the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada reveals that the two values of independence and accountability can co-exist. These nations use autonomous monitoring agencies, legislative mechanisms, and progressive penalties and maintain a high level of judicial independence. In the case of India, reform is not a question of choice anymore. The gap between autonomy and accountability would be closed by creating a statutory accountability structure, an independent oversight organ, through which it is represented, results of inquiry made public, and whistleblowers provided with proportionate penalties.

In the future, judicial integrity should continue being the foundation of the democratic trust. A plausible system of accountability will not diminish independence; on the contrary, it will make it stronger so that the judiciary will have the respect, legitimacy and confidence that constitutional democracy relies on in the end.

References

[1] INDIA CONST. art. 124(4); The Judges (Inquiry) Act, No. 51 of 1968, § 3.

[2] Supreme Court of India, In-House Procedure (1999) (on file with the Supreme Court Registry).

[3] Arun K. Thiruvengadam, Revisiting Judicial Accountability in India: The In-House Procedure and Beyond, 5 Indian J. Const. L. 123, 130–35 (2002).

[4] M.P. Jain, Indian Constitutional Law 336 (8th ed. 2018).

[5] INDIA CONST. art. 124(4).

[6] The Judges (Inquiry) Act, No. 51 of 1968, § 3 (India); The Judges (Inquiry) Rules, 1969.

[7] K. Veeraswami v. Union of India, (1991) 3 S.C.C. 655 (India).

[8] Saptarshi Mandal, The Supreme Court’s In-House Procedure and the Sexual Harassment Allegations Against Judges, 4 NUJS L. Rev. 255, 260–65 (2019).

[9] Supreme Court of India, In-House Procedure (1999) (on file with the Supreme Court Registry).

[10] P.P. Rao, Judicial Independence, Accountability, and the In-House Procedure, 41 JILI 1, 4–6 (1999).

[11] The Judges (Inquiry) Act, No. 51 of 1968, § 3, INDIA CODE (1968).

[12] Id. at 8–10.

[13] Justice J.S. Verma, Restoring Judicial Credibility: The Case for In-House Mechanisms, 42 JILI 12, 14 (2000).

[14] Arun K. Thiruvengadam, Revisiting Judicial Accountability in India: The In-House Procedure and Beyond, 5 Indian J. Const. L. 123, 132–36 (2002).

[15] S.P. Sathe, Judicial Activism in India: Transgressing Borders and Enforcing Limits 295–98 (2d ed. 2002).

[16] Pratap Bhanu Mehta, The Rise of Judicial Sovereignty, 18 J. Indian L. & Soc’y 67, 74–75 (2006).

[17] Supreme Court of India, In-House Procedure (1999) (on file with the Supreme Court Registry).

[18] Justice J.S. Verma, Restoring Judicial Credibility: The Case for In-House Mechanisms, 42 JILI 12, 15 (2000).

[19] Arun K. Thiruvengadam, Revisiting Judicial Accountability in India: The In-House Procedure and Beyond, 5 Indian J. Const. L. 123, 135–37 (2002).

[20] Judicial Conduct Investigations Office (UK), Annual Report 2021–22 (2022).

[21] S.P. Sathe, Judicial Activism in India: Transgressing Borders and Enforcing Limits 296–97 (2d ed. 2002).

[22] Law Commission of India, Report No. 230: Reforms in the Judiciary ¶ 7.3 (2009).

[23] In re: Justice C.S. Karnan, (2017) 7 S.C.C. 1 (India).

[24] Saptarshi Mandal, The Supreme Court’s In-House Procedure and the Sexual Harassment Allegations Against Judges, 4 NUJS L. Rev. 255, 262–67 (2019).

[25] Constitutional Reform Act, 2005, c. 4, §§ 108–115 (UK).

[26] Judicial Conduct Investigations Office, Annual Report 2021–22 (2022).

[27]Judicial Conduct and Disability Act of 1980, 28 U.S.C. §§ 351–364 (2018) (US). Judicial Conduct and Disability Act of 1980, 28 U.S.C. §§ 351–364 (2018) (US).

[28] Richard E. Flamm, Judicial Disqualification: Recusal and Disqualification of Judges 947–52 (2d ed. 2007).

[29] Judges Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. J-1, §§ 60–65 (Can.).

[30] Canadian Judicial Council, Report to the Minister of Justice on the Inquiry into the Conduct of Justice Robin Camp (2017).

[31] The Judicial Standards and Accountability Bill, Bill No. 131 of 2010, Lok Sabha (India).

[32] Law Commission of India, Report No. 230: Reforms in the Judiciary ¶ 7.4 (2009).

[33] Judicial Conduct Investigations Office, Annual Report 2021–22 (2022); Canadian Judicial Council, Annual Report 2020–21 (2021).

[34] Richard E. Flamm, Judicial Disqualification: Recusal and Disqualification of Judges 953–55 (2d ed. 2007).

[35] M.P. Jain, Indian Constitutional Law 342–43 (8th ed. 2018).

[36] Whistle Blowers Protection Act, No. 17 of 2014, INDIA CODE (2014).

[37] Justice J.S. Verma, Restoring Judicial Credibility: The Case for In-House Mechanisms, 42 JILI 12, 18–19 (2000).

[38] Canadian Judicial Council, Ethical Principles for Judges (2017).

Journal Volume

You should always try to find volume and issue number for journal articles.

Nyayavimarsha

No. 74/81, Sunderraja nagar,

Subramaniyapuram, Trichy- 620020