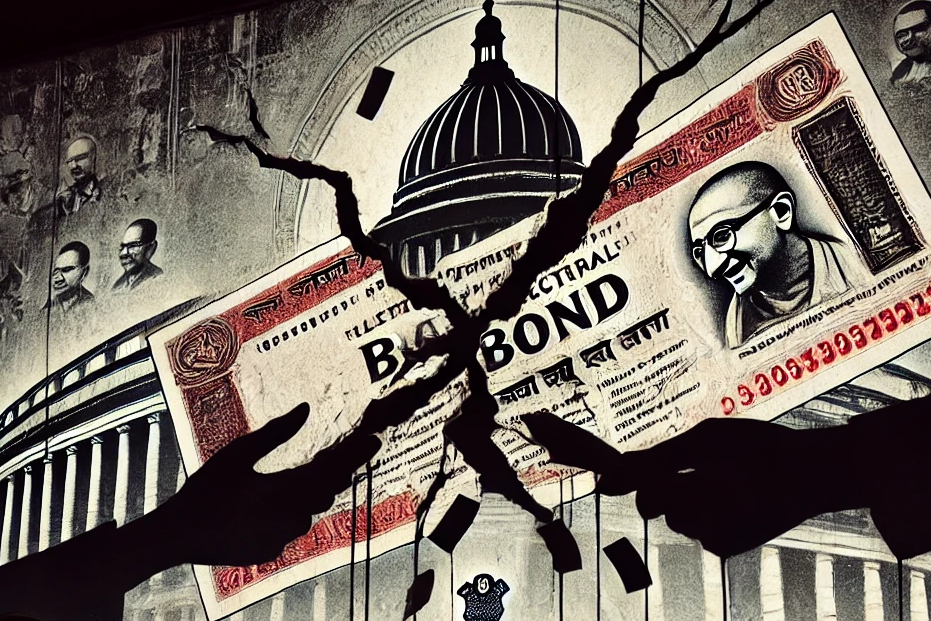

BEHIND THE VEIL: Unpacking the Controversy of the Electoral Bonds Scam

Published on : 26/09/2024

View Count : (118)

BEHIND THE VEIL:

Unpacking the Controversy of the Electoral Bonds Scam

Authored by: Ms. Parul Thakur

Law Student

Punjab University

mailto:parulthakur4170@gmail.com

Click here for copyrights policy

How can loss-making companies donate crores of funds through Electoral Bonds to political parties? How can companies donate more than their profits? How can newly set companies donate via electoral bonds when the statutes debar it? More than 20,000 electoral bonds were encashed by the political parties from April 1, 2019, till February 15, 2024, making the total donations jump over Rs. 12,000 Crores.[1] Contesting Elections is an expensive exercise in India and enormous funds are required. In the 2019 General Elections, the expenses almost ballooned to around Rs. 65,000 Crores, making it the world's most expensive election. Thus, huge funds are required by the political parties even to contest the elections. While legal frameworks exist to curtail election expenses for candidates and mandate the transparency of corporate donations to political parties, these provisions are often inadequately enforced or exploited due to legal loopholes. The 2001 Consultation Paper on Electoral Reforms by the NCRWC reveals the extent of this discrepancy, estimating that actual campaign spending by candidates surpasses the statutory limits by “approximately 20 to 30 times."[2]

These funds are allowed to be garnered by various donations to make the elections free and fair providing a level playing field to the candidates. But this exercise led to the channeling of black, unaccounted money and a quid pro quo system.

Electoral Bonds were introduced by the ruling government as a Scheme targeting to combat corruption and improve accountability and transparency through the Finance Bill of 2017 and subsequently, it was implemented in 2018. The scheme permitted both corporations and individuals to acquire electoral bonds—interest-free bearer instruments—and contribute them anonymously to political parties. This anonymity made the scheme an appealing method for political donations. However, public concerns have arisen regarding its potential to erode democratic values and foster corruption, given the secrecy surrounding donor identities. These bonds function in the same way as bearer bonds or promissory notes, with a bank acting as the issuer and custodian, while the political party, as the bondholder, receives the funds. Because electoral bonds are bearer instruments, no ownership information is registered, so the holder of the bond is considered its rightful owner. The donor's name and other identifying details are not listed on the bond, preserving the anonymity of the donation. These were available in the denominations of Rs.1,000, Rs.10,000, Rs.1,00,000, Rs.10,00,000, and Rs.1,00,00,000 and could be purchased only in the beginning 10 days of each quarter, i.e., in January, April, July, and October, as specified by the central government[3]. The government may designate an additional 15-day window for issuing electoral bonds during a general election year. The funding limit which was set to Rs. 20,000 earlier was brought down to Rs. 2,000. Any donations more than that will be required to disclose all the details of the donors. Moreover, the donors will only be able to donate to the political parties that are registered under Section 29A of the Representation of People Act, 1951, and have garnered at least 1% of votes in the last general elections. The parties then had 15 days to encash the electoral bonds in their designated SBI account. If this period passes, then the total amount of the bond is submitted to the PM Cares Fund.

The continuous debate for transparency and accountability for holding free and fair elections is unending. Transparency in electoral funding is a cornerstone of democratic principles. However, relying solely on digital transactions does not ensure a full proof check upon transparency. In practice, electoral bonds create a form of partial transparency, as donor information is exclusively held by the State Bank of India (SBI), a government-controlled statutory institution through which the ruling government can easily get the access to the donor information and can harass the donors who donated to the opposition parties.

The Indian government has openly acknowledged the infiltration of black money into election financing. The electoral bond scheme was introduced to curb this issue by enforcing digital transactions through regulated banking channels. These bonds are exclusively available at only designated 29 branches of the State Bank of India (SBI), the nation’s public-sector bank. The bonds do not bear the name of the payee but the entire database is kept with the SBI. While the data remains concealed from the general public and opposition parties, electoral bonds grant the ruling party privileged access through SBI, raising serious concerns about the fairness and transparency of the electoral process. This discrepancy between public secrecy and selective disclosure casts doubts on the scheme's alignment with democratic principles. In contrast to most liberal democracies, where political funding data is openly accessible, the veil of anonymity surrounding India’s electoral financing invites scrutiny and raises critical questions about its necessity.

Amidst these concerns, regulatory bodies like the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and the Election Commission of India (ECI) have issued cautionary advisories, warning of the vulnerability of electoral bonds to exploitation by shell companies for facilitating money laundering and illicit financial activities. The ECI has even opined electoral bonds as a regressive step, further leading to the blotting of transparent, free, and fair elections.

The idea of electoral bonds or political funding did not emerge from thin air. From 1951 itself, big business entities, like, Birlas, Thukurdas, TATA, etc have been funding Congress as it was the largest party present in the system then. Till the 1980s, only Bombay Dying’s Nusli Wadia supported the Bharatiya Janata Party due to its limited reach. An interesting argument was made on record by the TATA’s advocate, in the case of Jayantilal Ranchhoddas Koticha v. TISCO[4], filed by a shareholder of TISCO against the company for donating funds to a political party without even notifying the shareholders, that they have been donating their profits to the party to make sure that it stays in power and thus lends them support as well. Such power was also reflected when the Swatantra Party got the support of the industrialists and they were able to defeat Congress in 9 states.

Such scheming amongst the parties led to even banning of political funding to political parties by the Indira Gandhi Government but instead led to an influx of black money and a rise of illegal funding in the market. To combat the issue, the Rajiv Gandhi Government reformed the statutes and allowed political funding but with a maximum limit of 5% of a company’s average profit earned (which was eventually increased to 7.5%). The highest value a company could donate was limited to Rs. 25,000 and it was to be mentioned in the Annual Financial Reports of the Company.

The revelation of the names of the donors led to the troubling of those companies by the ruling party who funded the opposition, this led to the existence of the Electoral Trusts in which the companies pooled their profits and then funded the political parties. It acted as an unregulated buffer between the party and the donor. This again led to the rise of goons, unaccounted cash, and even politicians with criminal records. As struggled by the Association for Democratic Reforms[5], the Right to know the candidates for free and fair elections under Right to information was added by the Supreme Court. Further, the Representation of People Act, 1951 was also amended[6] to put a cap of Rs. 20,000 on donations in cash, and if more than that, then, the parties had to disclose the details of the donors. Again, the loophole of making receipts of less than Rs. 20,000 led to the defeat of the purpose of the legislation when all the audits were done by the parties themselves. ECI has also recommended that audits for the political parties should be done by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India as it involves public money.[7]

The Law Commission in its report on Electoral Reforms in 2015 mentioned that ADR has analysed that more than 75% of the sources of political funding were unknown in the General Elections of 2009.[8] Thus, to control the rapidly growing menace of corruption, black money and cash and to strengthen transparency, the government in 2017 tabled the idea of Electoral Bonds.

The scheme created a multiverse of controversies as it was implemented by inviting a myriad of amendments to the existing laws of the land. First and foremost, the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934 was amended by taking away their powers and granting the powers to SBI to issue Electoral Bonds. The Bill was introduced in the parliament as a ‘Money Bill’ but it was highly questioned as the bill did not meet the adequate eligibility to be qualified as a money bill. It was opined that it was done to surpass the scrutiny in Rajya Sabha where the government was weak. The Companies Act, 2013, was also amended to remove the upper limit a company was allowed to donate, which was earlier set at 7.5% of the average profits of the company. Now, they could even donate more than their earned profits. RBI and ECI in their discussions and statements have raised their concerns over how this setup was detrimental to the free and fair elections and democracy in the country[9], further even aiding in money laundering and the rise of shell companies, but the government conveniently disregarded their opinion. Law Commission also cautioned that eligibility of being able to receive funds will act as a hurdle to the smaller political parties for a fair opportunity to contest the elections. Concerns were also floated about the secret number present on the electoral bond which would defeat the entire purpose of anonymity. Critics posit that the ruling party's exclusive access to donor information discourages potential contributors from using electoral bonds to support opposition parties due to concerns of reprisal or intimidation.[10] While the BJP amassed approximately Rs. 6,540 Crore through electoral bonds, the leading opposition party, the Indian National Congress, secured only Rs. 1,122 Crore approximately. This stark imbalance intensifies demands for a reassessment of the scheme’s effectiveness and its ethical ramifications.

Soon after the amendments were introduced, in September 2017 and January 2018, two NGOs—Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) and Common Cause—along with the Communist Party of India (Marxist), filed petitions in the Supreme Court contesting the changes. The petitions argued that the Finance Acts had been improperly classified as money bills, circumventing thorough scrutiny by the Rajya Sabha. This challenge is also part of a broader dispute regarding using money bills under Article 110 of the Constitution. In addition to several other parties, even the Election Commission of India opposed the scheme, arguing that it would undermine transparency in political financing.

The petitioners further claimed that the scheme promoted "non-transparency in political funding" and enabled electoral corruption on a "large scale."

In its judgment overturning the Electoral Bond Scheme as unconstitutional, the Supreme Court addressed two central questions:

1. Whether the lack of transparency regarding voluntary contributions to political parties under the scheme, as well as amendments to Section 29C of the Representation of People Act, Section 182(3) of the Companies Act, and Section 13A(b) of the Income Tax Act, infringed upon citizens' Right to Information guaranteed by Article 19(1)(a) of the Indian Constitution?

2. Whether the amendment to Section 182(1) of the Companies Act, allowing unrestricted corporate donations to political parties, violated the principle of free and fair elections and contravened Article 14, which upholds the right to equality before the law?

The Court determined that the anonymity inherent in the Electoral Bond Scheme infringed upon the Right to Information enshrined in Article 19(1)(a) of the Indian Constitution, as it unduly restricted a voter's ability to discern the source of political party funding, thereby undermining the democratic right to vote. This rationale was central to the Court's decision to strike down the Scheme.

Article 19 of the Constitution allows for limitations on the Right to Information under Article 19(1)(a) only on specific grounds outlined in Article 19(2). The government defended the Electoral Bond Scheme, asserting that it fell within the permissible restrictions on the right to freedom of speech and expression. However, the Court rejected this argument, observing that the Scheme's purported objective of curbing the flow of black money in electoral financing did not correspond to any of the grounds in Article 19(2). Moreover, the Court found that the proportionality test—used to assess whether restrictions on a fundamental right are justified—was not satisfied in this instance. Even the least restrictive test was not followed in bringing about this scheme.

The Court further emphasized that the goal of mitigating black money could be achieved through alternative mechanisms, such as establishing an Electoral Trust. It proposed that an Electoral Trust could be specifically created to collect political contributions, subject to stringent conditions: (a) the donor’s name, address, account details, amount contributed, and mode of payment must be recorded; (b) contributions to Electoral Trusts should be made solely through bank drafts, electronic transfers, or cheques, with no cash donations permitted; and (c) the Trust must maintain comprehensive records of both donors and the beneficiaries of the funds. Additionally, the Court stipulated that donations under ₹25,000 could be made via cheques or electronic transfers, ensuring greater transparency and accountability in political funding.

In addressing the second issue, the Court found that the amendment to Section 182 of the Companies Act, permitted both profit- and loss-making companies to donate unlimited amounts to political parties. The Court deemed this amendment arbitrary for the following reasons:

a) Allowing corporations to make unlimited contributions gives them disproportionate power to influence policymaking, far outweighing the influence of individual donors.

b) Treating corporate entities and individuals equally in terms of political donations made the scheme fundamentally arbitrary.

The Court further noted that such unrestricted corporate donations, combined with their significant influence on the electoral process, undermined the principles of free and fair elections and political equality, which are rooted in the concept of "one person, one vote." Corporate donations, the Court argued, often serve as business transactions intended to secure future benefits. For instance, on November 10, 2022, India's Enforcement Directorate, apprehended P Sarath Chandra Reddy, an entrepreneur based in Hyderabad, on charges related to a liquor scandal in New Delhi. Just five days later, Aurobindo Pharma, where Reddy serves as a director, purchased electoral bonds valued at 50 million rupees.[11]

Moreover, the Court criticized the amendment for failing to differentiate between donations from profit-making and loss-making companies, highlighting that loss-making companies are more likely to donate in exchange for political favors, thus reinforcing the arbitrary nature of the amendment.

Following the Supreme Court’s annulment of the Scheme and the subsequent nullification of various related statutory amendments, several crucial directives were issued. The State Bank of India (SBI) was mandated to halt the issuance of electoral bonds. Additionally, SBI was required to deliver to the Election Commission of India detailed records of all electoral bonds purchased from April 12, 2019, to the present, including the identities of purchasers and the denominations of the bonds. Furthermore, SBI was encouraged to disclose information regarding the political parties that have received contributions through these bonds. Electoral bonds that remained unredeemed by political parties within their 15-day validity period were to be returned to the original buyers. Lastly, the Election Commission of India was instructed to publish the data provided by SBI on its official website by March 13, 2024. Thus, the scheme was declared unconstitutional and was removed.

In conclusion, the Electoral Bond Scheme, originally engineered to enhance transparency in political financing, has devolved into a highly contentious issue. While it intended to mitigate the flow of unregulated funds and bolster accountability mechanisms, the inherent anonymity feature has raised substantial concerns regarding its implications for transparency, equitable political competition, and the potential for systemic exploitation. The Supreme Court’s decision to strike down the scheme underscored its inadequacy in preserving democratic principles, particularly the Right to Information and the critical need for transparency in political financing. The scheme skewed political fairness and heightened fears over undue corporate influence on elections through unrestricted donations and insufficient disclosure. The subsequent directives represent a pivotal shift towards reinforcing the integrity of India’s electoral system, underscoring the necessity for transparent, accountable, and just political funding practices moving forward.

[1] Bose, P. (2024) Decoding electoral bonds data, The Hindu (2nd September 2024) https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/decoding-electoral-bonds-data/article67969866.ece

[2] NCRWC, A Consultation Paper on Review of Election Law, Processes, and Reform Options, (2001), https://legalaffairs.gov.in/sites/default/files/(VII)Review%20of%20Election%20Law,%20Processes%20and%20Reform%20Options.pdf

[3] Electoral Bonds Scheme Notification (2018) Print Release (05 September 2024) https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=175194

[4] Jayantilal Ranchhoddas Koticha v. TISCO, AIR 1958 BOMBAY 155

[5] Union of India v Association for Democratic Reforms and Another, 2002 (3) SCR 294

[6] Election and Other Related Laws (Amendment) Act, 2003, No. 46, Acts of Parliament, 2003, (India)

[7] Tiriya, Ms.S. (2011) Audit of political parties, (10 September 2024) https://sansad.in/getFile/annex/222/Au1172.pdf?source=pqars

[8] ADR, Electoral and Political Reforms, 6th September,2024 https://adrindia.org/sites/default/files/Electoral,%20Political%20Reforms%20and%20ADR.pdf

[9] Electoral bonds: Seeking secretive funds, Modi Govt overruled RBI (2019) The Reporters’ Collective, (10 September 2024) https://www.reporters-collective.in/stories/electoral-bonds-seeking-secretive-funds-modi-govt-overruled-rbi

[10] Purohit, K. (2024) What are India’s electoral bonds, the secret donations powering Modi’s BJP?, Al Jazeera, (12 September 2024) https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/2/15/what-are-electoral-bonds-the-secret-donations-powering-modis-bjp

[11] Sharma, Y. (2024) India’s electoral bonds laundry: ‘corrupt’ firms paid parties, got cleansed, Al Jazeera. (12 September 2024). https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/4/4/indias-electoral-bonds-laundry-corrupt-firms-paid-parties-got-cleansed

Journal Volume

You should always try to find volume and issue number for journal articles.